|

Mount Allan Aboriginal

Community |

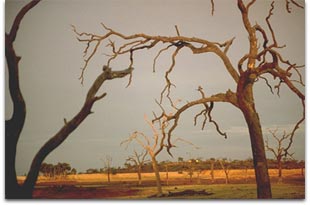

At first impression the landscape of Mount Allan is somewhat uninspiring,

with the flat terrain and the seemingly endless mulga scrub dominating

the eye. It is when the outcrops of red stone are approached that one begins

to appreciate the diversity and adaptability of the native vegetation.

Climb

onto one of these outcrops, and a stunning vista of rocky islands on

a sea of mulga is revealed. The native pines respond to the sun's golden

probes

with the most exquisite display of colour changes - green, blue and golden

- with their dark twisted trunks locked in an ancient dance against a

backdrop of rainbow pastel. At first impression the landscape of Mount Allan is somewhat uninspiring,

with the flat terrain and the seemingly endless mulga scrub dominating

the eye. It is when the outcrops of red stone are approached that one begins

to appreciate the diversity and adaptability of the native vegetation.

Climb

onto one of these outcrops, and a stunning vista of rocky islands on

a sea of mulga is revealed. The native pines respond to the sun's golden

probes

with the most exquisite display of colour changes - green, blue and golden

- with their dark twisted trunks locked in an ancient dance against a

backdrop of rainbow pastel.

The receding sun in the late afternoon reflects

off a billion facets

of stone, and the non stop display of colour changes amongst the vegetation

culminates in an awesome array of fiery red before the orb sinks below

the razor edge of blue hills, and the first twinkling star heralds

the display yet to come. From this magical desert landscape comes a wealth

of artistic

expression that is rich in ancient folklore and is unique to the rest

of

the world.

|

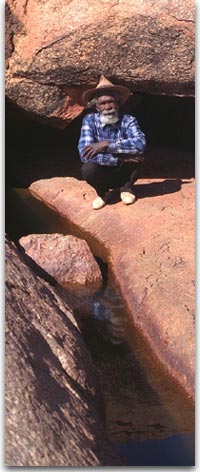

Old Cassidy Japaldjardi

at Ngarlu Rockhole |

Mount Allan Station

Mount Allan Station, 300 km from Alice Springs off

the Tanami Desert Track, is an Aboriginal owned and operated cattle

station. There is a

community store providing food and fuel for travellers and for the

250 people who live on Mount Allan, and a Primary school .

The successful promotion of the art and culture of the Anmatjerre people

provides a substantial source of revenue for the painters and the community

as a whole. Whether the paintings are telling of a dreamtime act of

creation, or of food-gathering or ceremonial events, they always relate

to particular

physical sites known to the artist, of immense importance to the bonding

they feel for the rugged countryside of the Mount Allan district.

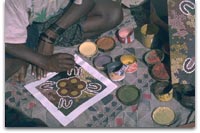

Ancient

Art - Modern Materials

Acrylic paintings have replaced the ochres,

clays and chalky pastes used for colouring in by-gone days, and canvas,

stretched on wooden

frames

has all but replaced the fleeting images told in sandpaintings.

It is for ceremonial occasions only - initiation ceremonies and corroborrees

- that traditional colouring ingredients are still used for the

creation

of the sacred, fleeting, sandpaintings. For acrylic paintings,

instead of the traditional twigs of yesteryear, the flat top of a paint

brush

is used to make the dots so prevalent in Western Desert art, but

the stories and symbolism remain the same. Circles, depicted in

rings of

dots, denote important sites such as trees, waterholes, camping

sites, or other physical features.

Curves in the paintings indicate groups of

people camping, or gathering food together, while small oval shapes

and stick-like figures denote

the tools used during food gathering. The tracks of animals feature

often in the stories, as well as body decorations worn during ceremonial

occasions.

The paintings are map-like in their depiction: i.e. there is no "top

or bottom " to the scenes they portray. Aboriginal desert art is

the newest, yet oldest, art form in the world today. Each painting is

a combination of tradition and innovation. The symbolism is both complex

and ambiguous to the uninitiated. In contemporary art terms, they are

incredibly dynamic and cosmic in their geometric abstraction.

Cultural Continuity

The increasing demand and recognition of the Aboriginal

desert art form by Western culture is helping to ensure that the skills

and the stories

survive, while at the same time helping to bridge the gap between the

two cultures. The financial reward for the art produced at Mount Allan

is an important component of the community's viability as the Aboriginal

people enter their third century of European occupation. Having no

traditional written language, the art is the means by which the dreamtime

stories

have been passed on for thousands of years. It is fitting that the

recognition for this work has never been higher, and ironic that white society's

belated interest may be the crucial ingredient necessary to keep the

dreaming alive forever.

Jack Cook Jungala

|